Page 118 - WDT Winter 2018 japan

P. 118

as symbols of a decrepit, degenerate past, and ordered them

torn down. Himeji was slated for demolition to make way for –

what else – new development, but it was eventually spared.

Besides its reputation as the grandest of Japan’s surviv-

ing castles, Himeji acquired an aura of having divine protec-

tion after it survived a World War II bombing attack. During

an aerial raid on Himeji city on July 3, 1945, a bomb struck the

castle but failed to explode, leaving the magnificent tower

intact while more than 60 percent of the city was incinerated.

When surviving residents emerged from the ashes and saw

the castle still standing, they drew inspiration from the fortress

and adopted it as a symbol of resilience. Sort of like a “Himeji

Strong.”

Getting to Himeji from our base in Osaka was easy, once

we had mastered the bullet train and Shin Osaka train station,

the major hub for Western Honshu island. Because Himeji

is small compared with major Japanese cities – about a half

million people – not all bullet trains stop there, so we had to

make sure to get to the right track. The train covered the 60

miles to Himeji in about a half hour.

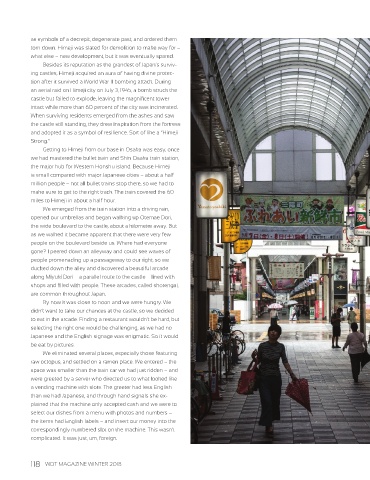

We emerged from the train station into a driving rain,

opened our umbrellas and began walking up Otemae Dori,

the wide boulevard to the castle, about a kilometer away. But

as we walked it became apparent that there were very few

people on the boulevard beside us. Where had everyone

gone? I peered down an alleyway and could see waves of

people promenading up a passageway to our right, so we

ducked down the alley and discovered a beautiful arcade

along Miyuki Dori – a parallel route to the castle – lined with

shops and filled with people. These arcades, called shotengai,

are common throughout Japan.

By now it was close to noon and we were hungry. We

didn’t want to take our chances at the castle, so we decided

to eat in the arcade. Finding a restaurant wouldn’t be hard, but

selecting the right one would be challenging, as we had no

Japanese and the English signage was enigmatic. So it would

be eat by pictures.

We eliminated several places, especially those featuring

raw octopus, and settled on a ramen place. We entered – the

space was smaller than the train car we had just ridden – and

were greeted by a server who directed us to what looked like

a vending machine with slots. The greeter had less English

than we had Japanese, and through hand signals she ex-

plained that the machine only accepted cash and we were to

select our dishes from a menu with photos and numbers –

the items had English labels – and insert our money into the

correspondingly numbered slot on the machine. This wasn’t

complicated. It was just, um, foreign.

118 WDT MAGAZINE WINTER 2018